Translated by Lisa Dillman

The alert was first raised at six in the morning: a fire was tearing through the El Bordo mine. After a short evacuation, the mouths of the shafts were sealed. Company representatives hastened to assert that “no more than ten” men remained in the shafts at the time of their closure, and Company doctors hastened to proclaim them dead. The El Bordo stayed shut for six days.

When the mine was opened there was a sea of charred bodies—men who had made it as far as the exit, only to find it shut. The final death toll was not ten, but eighty-seven. And there were seven survivors.

Now, a century later, acclaimed novelist Yuri Herrera has carefully reconstructed a worker’s tragedy at once globally resonant and deeply personal: Pachuca is his hometown. His sensitive and deeply humanizing work is an act of restitution for the victims and their families, bringing his full force of evocation to bear on the injustices that suffocated this horrific event into silence.

Review:

I jumped at the chance to read this book because I love Herrera’s novel Signs Preceding the End of the World, and I’m always excited to read nonfiction in translation. And read that jacket copy above – mine disaster! Intrigue!

I expected a wild ride but the book is subdued. An exhaustive investigation of the circumstances is impossible 100 years after the disaster so Herrera does the next best thing, critically examining the records left behind.

After outlining the sequence of events as well as we can know them, he looks at what isn’t in the record. How the stories of relatives, often women, are replaced with legalese. What the judge didn’t order investigated. How newspaper accounts were riddled with bias, to the point of obscuring all fact.

The book is a mere 120 pages long and as I reached the end I realized I probably read it too quickly. Some themes I picked up right away – how women were silenced and pushed aside, for example – but others I missed until the very end. Why didn’t I notice the pattern of Anglo names? Did I glance over something early that pointed to the fact that the mine was owned by a US company?

I’ll have to read this book again, at a slower pace, to pick up everything Herrera is putting down. If you’re expecting narrative twists and definite answers you’ll be disappointed. But if you don’t mind following the author has he wipes a century’s worth of dust off of a supposedly settled case he has interesting things to say.

Thanks to And Other Stories and Edelweiss for providing an advance copy.

Plucked from her life on the streets of post-apocalyptic Santo Domingo, young maid Acilde Figueroa finds herself at the heart of a Santería prophecy: only she can travel back in time and save the ocean – and humanity – from disaster. But first she must become the man she always was – with the help of a sacred anemone. Tentacle is an electric novel with a big appetite and a brave vision, plunging headfirst into questions of climate change, technology, Yoruba ritual, queer politics, poverty, sex, colonialism and contemporary art. Bursting with punk energy and lyricism, it’s a restless, addictive trip: The Tempest meets the telenovela.

Plucked from her life on the streets of post-apocalyptic Santo Domingo, young maid Acilde Figueroa finds herself at the heart of a Santería prophecy: only she can travel back in time and save the ocean – and humanity – from disaster. But first she must become the man she always was – with the help of a sacred anemone. Tentacle is an electric novel with a big appetite and a brave vision, plunging headfirst into questions of climate change, technology, Yoruba ritual, queer politics, poverty, sex, colonialism and contemporary art. Bursting with punk energy and lyricism, it’s a restless, addictive trip: The Tempest meets the telenovela. On Thursday, August 9, 1945, at two minutes past eleven in the morning, Nagasaki was wiped out by a plutonium atomic bomb which exploded at a height of five hundred meters over the city. Among the wounded on that fateful day was the young doctor Takashi Nagai, professor of radiology at the University of Nagasaki. Nagai succeeded in gathering a tiny group of survivors — doctors, nurses, and students — and together they worked heroically for the wounded until they themselves collapsed from exhaustion and atomic sickness.

On Thursday, August 9, 1945, at two minutes past eleven in the morning, Nagasaki was wiped out by a plutonium atomic bomb which exploded at a height of five hundred meters over the city. Among the wounded on that fateful day was the young doctor Takashi Nagai, professor of radiology at the University of Nagasaki. Nagai succeeded in gathering a tiny group of survivors — doctors, nurses, and students — and together they worked heroically for the wounded until they themselves collapsed from exhaustion and atomic sickness. Zsófia Ban’s Night School: A Reader for Adults uses a textbook format to build an encyclopedia of life—subject by subject, from self-help to geography to chemistry to French. With subtle irony, Ban’s collection of “lectures” guides readers through the importance and uses of the power of Nohoo (or “know-how”), tells of the travels of young Flaubert to Egypt with his friend Maxime, and includes a missive from Laika the dog minutes before being blasted off into space, never to be seen again. A wildly clever book that makes our all-too-familiar world appear simultaneously foreign and untamed, and brings together lust, taboos, and the absurd in order to teach us the art of living.

Zsófia Ban’s Night School: A Reader for Adults uses a textbook format to build an encyclopedia of life—subject by subject, from self-help to geography to chemistry to French. With subtle irony, Ban’s collection of “lectures” guides readers through the importance and uses of the power of Nohoo (or “know-how”), tells of the travels of young Flaubert to Egypt with his friend Maxime, and includes a missive from Laika the dog minutes before being blasted off into space, never to be seen again. A wildly clever book that makes our all-too-familiar world appear simultaneously foreign and untamed, and brings together lust, taboos, and the absurd in order to teach us the art of living. A housewife takes up bodybuilding and sees radical changes to her physique–which her workaholic husband fails to notice. A boy waits at a bus stop, mocking businessmen struggling to keep their umbrellas open in a typhoon–until an old man shows him that they hold the secret to flying. A woman working in a clothing boutique waits endlessly on a customer who won’t come out of the fitting room–and who may or may not be human. A newlywed notices that her husband’s features are beginning to slide around his face–to match her own.

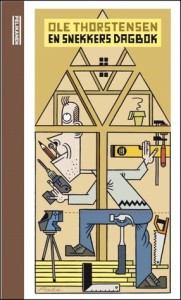

A housewife takes up bodybuilding and sees radical changes to her physique–which her workaholic husband fails to notice. A boy waits at a bus stop, mocking businessmen struggling to keep their umbrellas open in a typhoon–until an old man shows him that they hold the secret to flying. A woman working in a clothing boutique waits endlessly on a customer who won’t come out of the fitting room–and who may or may not be human. A newlywed notices that her husband’s features are beginning to slide around his face–to match her own. Making Things Right is the simple yet captivating story of a loft renovation, from the moment master carpenter and contractor Ole Thorstensen submits an estimate for the job to when the space is ready for occupation. As the project unfolds, we see the construction through Ole’s eyes: the meticulous detail, the pesky splinters, the problem solving, patience, and teamwork required for its completion. Yet Ole’s narrative encompasses more than just the fine mechanics of his craft. His labor and passion drive him toward deeper reflections on the nature of work, the academy versus the trades, identity, and life itself.

Making Things Right is the simple yet captivating story of a loft renovation, from the moment master carpenter and contractor Ole Thorstensen submits an estimate for the job to when the space is ready for occupation. As the project unfolds, we see the construction through Ole’s eyes: the meticulous detail, the pesky splinters, the problem solving, patience, and teamwork required for its completion. Yet Ole’s narrative encompasses more than just the fine mechanics of his craft. His labor and passion drive him toward deeper reflections on the nature of work, the academy versus the trades, identity, and life itself. I ran into a few issues, though. Unfortunately the translation and audiobook narration do not mesh well. It sounds like a British English translation read by someone who knows Norwegian and speaks with an American accent. On top of that it sounds like some terms were slapdash “translated” into American without much thought.

I ran into a few issues, though. Unfortunately the translation and audiobook narration do not mesh well. It sounds like a British English translation read by someone who knows Norwegian and speaks with an American accent. On top of that it sounds like some terms were slapdash “translated” into American without much thought. Huzzah for August, Women in Translation Month! This is the month to read works in translation by women, trans, and non-binary folk. Precious few books in English are translations, and only a quarter or so of those are by women. Summer is the perfect time to highlight these amazing books and let the world know how awesome women authors (and translators!) are.

Huzzah for August, Women in Translation Month! This is the month to read works in translation by women, trans, and non-binary folk. Precious few books in English are translations, and only a quarter or so of those are by women. Summer is the perfect time to highlight these amazing books and let the world know how awesome women authors (and translators!) are.

The Farm in the Green Mountains by Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer, translated by Ida H. Washington

The Farm in the Green Mountains by Alice Herdan-Zuckmayer, translated by Ida H. Washington Chi’s Sweet Home by Kanata Konami (I can’t find the translator, gah)

Chi’s Sweet Home by Kanata Konami (I can’t find the translator, gah) The Master Key by Masako Togawa, translated by Simon Grove

The Master Key by Masako Togawa, translated by Simon Grove Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori Ten Women by Marcela Serrano, translated by Beth Fowler

Ten Women by Marcela Serrano, translated by Beth Fowler The Lonesome Bodybuilder by Yukiko Motoya, translated by Asa Yoneda

The Lonesome Bodybuilder by Yukiko Motoya, translated by Asa Yoneda False Calm: A Journey Through the Ghost Towns of Patagonia by María Sonia Cristoff, translated by Katherine Silver

False Calm: A Journey Through the Ghost Towns of Patagonia by María Sonia Cristoff, translated by Katherine Silver A young man’s close-knit family is nearly destitute when his uncle founds a successful spice company, changing their fortunes overnight. As they move from a cramped, ant-infested shack to a larger house on the other side of Bangalore, and try to adjust to a new way of life, the family dynamic begins to shift. Allegiances realign; marriages are arranged and begin to falter; and conflict brews ominously in the background.

A young man’s close-knit family is nearly destitute when his uncle founds a successful spice company, changing their fortunes overnight. As they move from a cramped, ant-infested shack to a larger house on the other side of Bangalore, and try to adjust to a new way of life, the family dynamic begins to shift. Allegiances realign; marriages are arranged and begin to falter; and conflict brews ominously in the background. In a surreal, but familiar, vision of modern day Egypt, a centralized authority known as ‘the Gate’ has risen to power in the aftermath of the ‘Disgraceful Events,’ a failed popular uprising. Citizens are required to obtain permission from the Gate in order to take care of even the most basic of their daily affairs, yet the Gate never opens, and the queue in front of it grows longer.

In a surreal, but familiar, vision of modern day Egypt, a centralized authority known as ‘the Gate’ has risen to power in the aftermath of the ‘Disgraceful Events,’ a failed popular uprising. Citizens are required to obtain permission from the Gate in order to take care of even the most basic of their daily affairs, yet the Gate never opens, and the queue in front of it grows longer. e by women so this is a time to draw attention to the awesomeness that’s out there and celebrate it. And because it’s a look at marginalized voices transgender and nonbinary authors are included in the mix, huzzah!

e by women so this is a time to draw attention to the awesomeness that’s out there and celebrate it. And because it’s a look at marginalized voices transgender and nonbinary authors are included in the mix, huzzah! Seeing Red

Seeing Red The First Wife

The First Wife